Mkpasswd For Mac

Mkpasswd はランダムな文字列でパスワードを生成できるコマンドです。インストールは mkpasswd ではなく expect で行ないます。 $ brew install homebrew/dupes/expect # Mac $ sudo yum install expect # CentOS. Passwords that are easy to remember and used multiple times are for suckers. Writing them down to type back in, or copy-pasting them each time is not only a hassle, it's a disaster waiting to happen. Here are the best password manager apps for Mac so that you can keep 'em secret and keep 'em safe.

- Mkpasswd For Mac Os

- Mkpasswd Mac Brew

- Mkpasswd For Mac N

- Mkpasswd For Mac Download

- Mkpasswd For Mac 2017

Ansible is a configuration management and provisioning tool, similar to Chef, Puppet or Salt.

I’ve found it to be one of the simplest and the easiest to get started with. A lot of this is because it’s “just SSH”; It uses SSH to connect to servers and run the configured Tasks.

One nice thing about Ansible is that it’s very easy to convert bash scripts (still a popular way to accomplish configuration management) into Ansible Tasks. Since it’s primarily SSH based, it’s not hard to see why this might be the case – Ansible ends up running the same commands.

We could just script our own provisioners, but Ansible is much cleaner because it automates the process of getting context before running Tasks. With this context, Ansible is able to handle most edge cases – the kind we usually take care of with longer and increasingly complex scripts.

Ansible Tasks are idempotent. Without a lot of extra coding, bash scripts are usually not safety run again and again. Ansible uses “Facts”, which is system and environment information it gathers (“context”) before running Tasks.

Ansible uses these facts to check state and see if it needs to change anything in order to get the desired outcome. This makes it safe to run Ansible Tasks against a server over and over again.

Here I’ll show how easy it is to get started with Anible. We’ll start basic and then add in more features as we improve upon our configurations.

Install

Of course we need to start by installing Ansible. Tasks can be run off of any machine Ansible is installed on.

This means there’s usually a “central” server running Ansible commands, although there’s nothing particularly special about what server Ansible is installed on. Ansible is “agentless” – there’s no central agent(s) running. We can even run Ansible from any server; I often run Tasks from my laptop.

Here’s how to install Ansible on Ubuntu 14.04. We’ll use the easy-to-remember ppa:ansible/ansible repository as per the official docs.

Ansible has a default inventory file used to define which servers it will be managing. After installation, there’s an example one you can reference at /etc/ansible/hosts.

I usually copy and move the default one so I can reference it later:

sudo mv /etc/ansible/hosts /etc/ansible/hosts.orig

Then I create my own inventory file from scratch. After moving the example inventory file, create a new /etc/ansible/hosts file, and define some servers to manage. Here’s we’ll define two servers under the “web” label:

For testing this article, I created a virtual machine, installed Ansible, and then ran Ansible Tasks directly on that server. To do this, my hosts inventory file simply looked like this:

Basic: Running Commands

Once we have an inventory configured, we can start running Tasks against the defined servers.

Ansible will assume you have SSH access available to your servers, usually based on SSH-Key. Because Ansible uses SSH, the server it’s on needs to be able to SSH into the inventory servers. It will attempt to connect as the current user it is being run as. If I’m running Ansible as user vagrant, it will attempt to connect as user vagrant on the other servers.

If Ansible can directly SSH into the managed servers, we can run commands without too much fuss:

If we need to define the user and perhaps some other settings in order to connect to our server, we can. When testing locally on Vagrant, I use the following:

Ansible uses “modules” to accomplish most of its Tasks. Modules can do things like install software, copy files, use templates and much more.

Modules are the way to use Ansible, as they can use available context (“Facts”) in order to determine what actions, if any need to be done to accomplish a Task.

If we didn’t have modules, we’d be left running arbitrary shell commands like this:

ansible all -s -m shell -a ‘apt-get install nginx’

Here, the sudo apt-get install nginx command will be run using the “shell” module. The -a flag is used to pass any arguments to the module. I use -s to run this command using sudo.

However this isn’t particularly powerful. While it’s handy to be able to run these commands on all of our servers at once, we still only accomplish what any bash script might do.

If we used a more appropriate module instead, we can run commands with an assurance of the result. Ansible modules ensure indempotence – we can run the same Tasks over and over without affecting the final result.

For installing software on Debian/Ubuntu servers, the “apt” module will run the same command, but ensure idempotence.

The result of running the Task was “changed”: false. This shows that there were no changes; I had already installed Nginx. I can run this command over and over without worrying about it affecting the desired result.

Going over the command:

all – Run on all defined hosts from the inventory file

-s – Run using sudo

-m apt – Use the apt module

-a ‘pkg=nginx state=installed update_cache=true’ – Provide the arguments for the apt module, including the package name, our desired end state and whether to update the package repository cache or not

We can run all of our needed Tasks (via modules) in this ad-hoc way, but let’s make this more managable. We’ll move this Task into a Playbook, which can run and coordinate multiple Tasks.

Basic Playbook

Playbooks can run multiple Tasks and provide some more advanced functionality that we would miss out on using ad-hoc commands. Let’s move the above Task into a playbook.

Playbooks and Roles in Ansible all use Yaml.

Create file nginx.yml:

$ ansible-playbook -s nginx.yml

PLAY [local] ******************************************************************

GATHERING FACTS ***************************************************************

ok: [127.0.0.1]

TASK: [Install Nginx] *********************************************************

ok: [127.0.0.1]

PLAY RECAP ********************************************************************

127.0.0.1 : ok=2 changed=0 unreachable=0 failed=0

Use use -s to tell Ansible to use sudo again, and then pass the Playbook file.

We get some useful feedback while this runs, including the Tasks Ansible runs and their result. Here we see all ran OK, but nothing was changed. I have Nginx installed already.

I used the command $ ansible-playbook -s -k -u vagrant nginx.yml to run this playbook locally on my Vagrant installation.

Handlers

A Handler is exactly the same as a Task (it can do anything a Task can), but it will run when called by another Task. You can think of it as part of an Event system; A Handler will take an action when called by an event it listens for.

This is useful for “secondary” actions that might be required after running a Task, such as starting a new service after installation or reloading a service after a configuration change.

Then we can create the Handler called “Start Nginx”. This Handler is the Task called when “Start Nginx” is notified.

This particular Handler uses the Service module, which can start, stop, restart, reload (and so on) system services. Here we simply tell Ansible that we want Nginx to be started.

Note that Ansible has us define the state you wish the service to be in, rather than defining the change you want. Ansible will decide if a change is needed, we just tell it the desired result.

Let’s run this Playbook again:

Notifiers are only run if the Task is run. If I already had Nginx installed, the Install Nginx Task would not be run and the notifier would not be called.

We can use Playbooks to run multiple Tasks, add in variables, define other settings and even include other playbooks.

More Tasks

Next we can add a few more Tasks to this Playbook and explore some other functionality.

The “Add Nginx Repository” Task registers “ppastable”. Then we use that to inform the Install Nginx Task to only run when the registered “ppastable” Task is successful. This allows us to conditionally stop Ansible from running a Task.

We also use a variable. The docroot variable is defined in the var section. It’s then used as the destination argument of the file module which creates the defined directory.

Mkpasswd For Mac Os

This playbook can be run with the usual command:

Roles

Roles are good for organizing multiple, related Tasks and encapsulating data needed to accomplish those Tasks. For example, installing Nginx may involve adding a package repository, installing the package and setting up configuration. We’ve seen installation in action in a Playbook, but once we start configuring our installations, the Playbooks tend to get a little more busy.

The configuration portion often requires extra data such as variables, files, dynamic templates and more. These tools can be used with Playbooks, but we can do better immediately by organizing related Tasks and data into one coherent structure: a Role.

Roles have a directory structure like this:

rolename

– files

– handlers

– meta

– templates

– tasks

– vars

Within each directory, Ansible will search for and read any Yaml file called main.yml automatically.

We’ll break apart our nginx.yml file and put each component within the corresponding directory to create a cleaner and more complete provisioning toolset.

Files

First, within the files directory, we can add files that we’ll want copied into our servers. For Nginx, I often copy H5BP’s Nginx component configurations. I simply download the latest from Github, make any tweaks I want, and put them into the files directory.

nginx

– files

– – h5bp

As we’ll see, these configurations will be added via the copy module.

Handlers

Inside of the handlers directory, we can put all of our Handlers that were once within the nginx.yml Playbook.

Inside of handlers/main.yml:

Meta

The main.yml file within the meta directory contains Role meta data, including dependencies.

If this Role depended on another Role, we could define that here. For example, I have the Nginx Role depend on the SSL Role, which installs SSL certificates.

Otherwise we can omit this file, or define the Role as having no dependencies:

Template files can contain template variables, based on Python’s Jinja2 template engine. Files in here should end in .j2, but can otherwise have any name. Similar to files, we won’t find a main.yml file within the templates directory.

Here’s an example Nginx virtual host configuration. Note that it uses some variables which we’ll define later in the vars/main.yml file.

Nginx virtual host file found at templates/serversforhackers.com.conf:

domain

ssl_crt

ssl_key

These three will be defined in the variables section.

Variables

Before we look at the Tasks, let’s look at variables. The vars directory contains a main.yml file which simply lists variables we’ll use. This provides a convenient place for us to change configuration-wide settings.

Here’s what the vars/main.yml file might look like:

domain: serversforhackers.com

ssl_key: /etc/ssl/sfh/sfh.key

ssl_crt: /etc/ssl/sfh/sfh.crt

These are three variables which we can use elsewhere in this Role. We saw them used in the template above, but we’ll see them in our defined Tasks as well.

Tasks

Let’s finally see this all put together into a series of Tasks.

Inside of tasks/main.yml:

Add the nginx/stable repository

Install & start Nginx, register successful installation to trigger remaining Tasks

Add H5BP configuration

Disable the default virtual host by removing the symlink to the default file from the sites-enabled directory

Copy the serversforhackers.com.conf.j2 virtual host template into the Nginx configuration

Enable the virtual host configuration by symlinking it to the sites-enabled directory

Create the web root

Change permission for the project root directory, which is one level above the web root created previously

There’s some new modules (and new uses of some we’ve covered), including copy, template, & file. By setting the arguments for each module, we can do some interesting things such as ensuring files are “absent” (delete them if they exist) via state=absent, or create a file as a symlink via state=link. You should check the docs for each module to see what interesting and useful things you can accomplish with them.

Running the Role

Before running the Role, we need to tell Ansible where our Roles are located. In my Vagrant server, they are located within /vagrant/ansible/roles. We can add this file path to the /etc/ansible/ansible.cfg file:

roles_path = /vagrant/ansible/roles

Assuming our nginx Role is located at /vagrant/ansible/roles/nginx, we’ll be all set to run this Role!

Remove the ssl dependency from meta/main.yml before running this Role if you are following along.

Let’s create a “master” yaml file which defines the Roles to use and what hosts to run them on:

File server.yml:

Facts

Before running any Tasks, Ansible will gather information about the system it’s provisioning. These are called Facts, and include a wide array of system information such as the number of CPU cores, available ipv4 and ipv6 networks, mounted disks, Linux distribution and more.

Facts are often useful in Tasks or Tempalte configurations. For example Nginx is commonly set to use as any worker processors as there are CPU cores. Knowing this, you may choose to set your template of the nginx.conf file like so:

user www-data www-data;

worker_processes {% verbatim %}{{ ansible_processor_cores }}{% endverbatim %};

pid /var/run/nginx.pid;

Or if you have a server with multiple CPU’s, you can use:

user www-data www-data;

worker_processes {% verbatim %}{{ ansible_processor_cores * ansible_processor_count }}{% endverbatim %};

pid /var/run/nginx.pid;

Ansible facts all start with anisble_ and are globally available for use any place variables can be used: Variable files, Tasks, and Templates.

Example: NodeJS

For Ubuntu, we can get the latest stable NodeJS and NPM from NodeSource, which has teamed up with Chris Lea. Chris ran the Ubuntu repository ppa:chris-lea/node.js, but now provides NodeJS via NodeSource packages. To that end, they have provided a shells script which installs the latest stable NodeJS and NPM on Debian/Ubuntu systems.

This shellscript is found at https://deb.nodesource.com/setup. We can take a look at this and convert it to the following tasks from a NodeJS Role:

First we create the Ensure Ubuntu Distro is Supported task, which uses the ansible_distribution_release Fact. This gives us the Ubuntu release, such as Precise or Trusty. If the resulting URL exists, then we know our Ubuntu distribution is supported and can continue. We register distrosupported so we can test if this step was successfully on subsequent tasks.

Then we run a series of tasks to remove NodeJS repositories in case the system already has ppa:chris-lea/node.js added. These only run when if the distribution is supported via when: distrosupported|success. Note that most of these continue to use the ansible_distribution_release Fact.

Finally we get the debian source packages and install NodeJS after updating the repository cache. This will install the latest stable of NodeJS and NPM. We know it will get the latest version available by using state=latest when installing the nodejs package.

Vault

We often need to store sensitive data in our Ansible templates, Files or Variable files; It unfortunately cannot always be avoided. Ansible has a solution for this called Ansible Vault.

Vault allows you to encrypt any Yaml file, which typically boil down to our Variable files. Vault will not encrypt Files and Templates.

When creating an encrypted file, you’ll be asked a password which you must use to edit the file later and when calling the Roles or Playbooks.

For example we can create a new Variable file:

ansible-vault create vars/main.yml

Vault Password:

After entering in the encryption password, the file will be opened in your default editor, usually Vim.

The editor used is defined by the EDITOR environmental variable. The default is usually Vim. If you are not a Vim user, you can change it quickly by setting the environmental variabls:

export EDITOR=nano

ansible-vault edit vars/main.yml

T> The editor can be set in the users profile/bash configuration, usually found at ~/.profile, ~/.bashrc, ~/.zshrc or similar, depending on the shell and Linux distribution used.

Ansible Vault itself is fairly self-explanatory. Here are the commands you can use:

$ ansible-vault -h

Usage: ansible-vault [create|decrypt|edit|encrypt|rekey]

[–help] [options] file_name

Options:

-h, –help show this help message and exit

For the most part, we’ll use ansible-vault create|edit /path/to/file.yml. Here, however, are all of the available commands:

create – Create a new file and encrypt it

decrypt – Create a plaintext file from an encrypted file

edit – Edit an already-existing encrypted file

encrypt – Encrypt an existing plain-text file

rekey – Set a new password on a encrypted file

Example: Users

I use Vault when creating new users. In a User Role, you can set a Variable file with users’ passwords and a public key to add to the users’ authorized_keys file (thus giving you SSH access).

T> Public SSH keys are technically safe for the general public to see – all someone can do with them is allow you access to their own servers. Public keys are intentionally useless for gaining access to a sytem without the paired private key, which we are not putting into this Role.

Here’s an example variable file which can be created and encrypt with Vault. While editing it, it’s of course in plain-text:

admin_password: $6$lpQ1DqjZQ25gq9YW$mHZAmGhFpPVVv0JCYUFaDovu8u5EqvQi.Ih

deploy_password: $6$edOqVumZrYW9$d5zj1Ok/G80DrnckixhkQDpXl0fACDfNx2EHnC

common_public_key: ssh-rsa ALongSSHPublicKeyHere

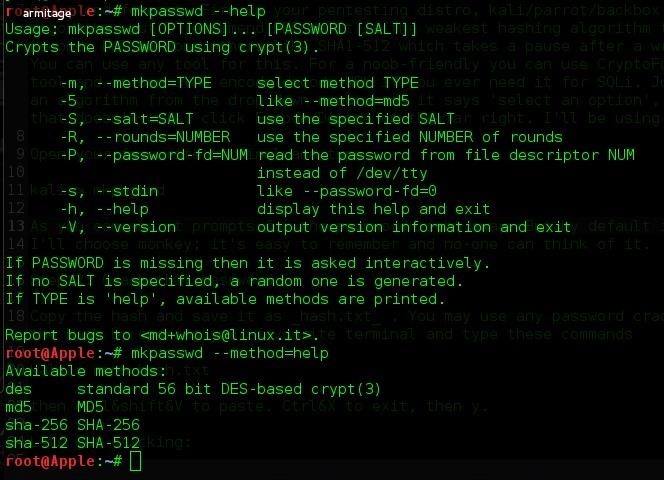

Note that the passwords for the users are also hashed. You can read Ansible’s documentation on generating encrypted passwords, which the User module requires to set a user password. As a quick primer, it looks like this:

$ sudo apt-get install -y whois

$ mkpasswd –method=SHA-512

Password:

This will generate a hashed password for you to use with the user module.

Mkpasswd Mac Brew

Once you have set the user passwords and added the public key into the Variables file, we can make a Task to use these encrypted variables:

It also uses the authorized_key module to add the SSH pulic key as an authorized SSH key in the server for each user.

Variables are used like usual within the Tasks file. However, in order to run this Role, we’ll need to tell Ansible to ask for the Vault password so it can unencrypt the variables.

Let’s setup a provision.yml Playbook file to call our user Role:

Mkpasswd For Mac N

ansible-playbook –ask-vault-pass provision.yml

Recap

Mkpasswd For Mac Download

Here’s what we did:

Mkpasswd For Mac 2017

- Installed Ansible

- Configured Ansible inventory

- Ran idempotent ad-hoc commands on multiple servers simultaneously

- Created a basic Playbook to run multiple Tasks, using Handlers

- Abstracted the Tasks into a Role to keep everything Nginx-related organized

- Saw how to set dependencies

- Saw how to register Task “dependencies” and run other Tasks only if they are successful

- Saw how to use more templates, files and variables in our Tasks

- Saw how to incorporate Ansible Facts

- Saw how to use Ansible Vault to add security to our variables